Last Friday, Andy and I attended a panel discussion about how to create a sustainable food system. We learned about the ways that farm workers here in Canada have been shipped in as cheap labor through temporary foreign worker programs, but are denied the basic protections that most people enjoy at their jobs—like paid vacation time, or overtime pay. “Piece rates,” rather than minimum wage, determine their income, and these rates are so low that half the workforce can’t pick produce fast enough to even make minimum wage! Workers are also at the mercy of unscrupulous contractors who function as the middlemen between farms and laborers, retaliating with job termination if workers complain about their housing, working conditions, or pay.

A priest running a migrant worker shelter two borders south, in Tijuana, Mexico, described the even larger problems facing agricultural workers in the United States. The U.S. economy depends on foreign labor, but unlike Canada, has no program for temporary workers at all. The result, he says, is an immigration system in chaos. 600,000 workers were deported from the U.S. last year. Many of them end up at the priest’s shelter, bewildered by their sudden twist of fate, separated from spouses and children, and—in many cases—finding themselves in Mexico for the first time in their lives. The priest told us about a surprising new industry popping up in Tijuana: call centers to employ the growing number of new deportees who speak better English than Spanish.

A small-scale farmer in Mexico (photo from Google images)

Ironically, it was an American-led free trade agreement which created the surge of illegal immigration from Mexico in the first place. When the North American Free Trade agreement (NAFTA) went into effect back in 1994, farming markets were opened so that peasant farmers in Mexico were suddenly competing against large, government-subsidized corn growers in the American Midwest. These small farmers couldn’t compete with the cheap imports from large-scale commercial farms in the U.S., and many of them went bust. Failed farms forced people to migrate first to Mexico’s cities, and then north to the U.S. looking for work. In the last ten years, narcotics cartels have intensified the problem by pushing even more Mexican farmers off their land and causing even urban dwellers to flee the threat of violence.

Corn had been the staple crop in Mexico for centuries. (photo from Google images)

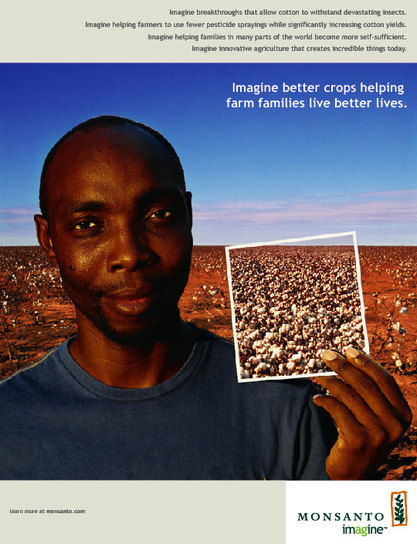

Finally, the director of the Domestic Fair Trade Association (DFTA) in Seattle, Washington, discussed the connection between the plight of small farmers in the U.S. and migrant farm workers from Latin America. Both are losing out against large-scale agribusiness, she says, and their best hope protecting their livelihoods is to band together to defend their rights against corporate giants like Monsanto. The DFTA is hoping to create these kinds of mutually beneficial partnerships all along the supply chain, connecting workers, farmers, suppliers, retailers, and consumers to work for the common good rather than pursuing their own economic benefit at the expense of others.

I have long been aware of the importance of buying fair trade when it comes to products imported from the developing world, such as coffee or chocolate. But this panel discussion opened my eyes to the reality that the agricultural sector here at home is hardly different from the unethical systems that prevail in other parts of the world.

The U.S. and Canada are wealthy, developed nations, but we are still depending on an underpaid, overworked labor force for our cheap, abundant food. Our laws do little to protect farm workers from exposure to harmful chemicals, abuse at the hands of their employers, and nonpayment of wages, and our legal system similarly lags behind in protecting the rights of small farmers.

These are serious problems that should concern anyone who eats food. The United States has an aging farm population, and we have reached a point as a society where we have more people in prison than we do on farms (an absurdity on both counts). According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the general population has a life expectancy of 73, but the average migrant farm worker can only expect to live to the age of 49. Furthermore, EPA safety standards for farm workers haven’t been updated in twenty years.

It’s obvious in our laws and in the way we have structured our economy that we don’t value the people who produce our food. We have come to see them as just another inanimate, economic input; something to be squeezed for as much productivity on as little pay as possible, to keep profit margins high and prices low for consumers like us.

There is currently no federal regulation for fair trade.

Think about that for a moment.

Farms—companies of all kinds—are under no obligation to prove that their products have been created without exploiting the people or the natural landscapes of the places where they were produced. There’s no way for us to know whether the food that we’re eating has poisoned a river, poisoned someone else’s body, or relied on slave labor to make it to our plate.

It’s high time fair trade came home to North America. We have a responsibility as North Americans and as Christians to care for the people who are sustaining our lives while barely being able to eek out a life of their own in the most prosperous nations on earth.

The video below features interviews from small farmers and migrant workers in the American South, and follows the story of a farm in Florida that is becoming part of the solution: