This is the second week of Advent, the season of waiting for Christ to come to us in the midst of our darkness. Having spent the last several years getting to know people in poverty and on the margins of society, I am pretty much constantly aware of that darkness, and it is sometimes easy to lose sight of the light altogether. That’s why I want to hold onto any glimpses I catch of the kingdom slowly but surely breaking in, and I want to share a few of them here.

I recently completed a three-month volunteer training with Battered Women’s Support Services here in Vancouver, where my fellow trainees were a group of brave women with beautiful, compassionate hearts. Most of those women don’t identify as people of faith, but I felt the presence of God in the midst of the safe and loving community we built together. That strong sense of community was absolutely vital during the twelve intense weeks we spent staring injustice and violence in the face and sharing some very raw pieces of our own stories. Exploring the ugliness of the world with a bunch of people who are committed to doing something about it helps keep my hope alive, and reminds me that there is strength in our shared vulnerability as human beings.

I’ve now begun fielding calls on the crisis line. From police to hospitals to courts, it’s been sobering to realize how often the systems that have been set up to protect the vulnerable actually let people slip through the cracks–or worse, further traumatize and isolate them. Sometimes, people struggling with mental health issues are given criminal records instead of help. Sometimes women are arrested for defending themselves against abusive partners while the men who batter them go free. I know this now, not only through statistics or reading articles or listening to experts talk about it, but from speaking to these women on the phone. All too often, factors such as race, income level, and immigration status determine whether or not a woman will get the help she needs.

Volunteering with BWSS has been a steep learning curve, and the stories of violence and abuse that I have been hearing over the phone are heartbreaking. Yet I also feel an overwhelming sense of gratitude for the chance to support these brave, resilient women in resisting violence and pursuing lives of dignity and safety. I am humbled by their tenacity in working against staggering odds to reclaim their own identities and the lives and to heal from trauma.

In other news, I’ve just landed my first paid job in Canada! Yesterday, I accepted a position working directly with refugee claimants: people who have fled their countries of origin because of violence or persecution based on their race, religion, nationality, political opinions or membership in a particular social group. In contrast to privately-sponsored or government-assisted refugees, refugee claimants undertake their dangerous journey without knowing whether or not they will be granted asylum when they reach their destination. They often face detention upon arrival, and the months-long refugee claims process that follows can be a stressful and scary time while claimants struggle to navigate an unfamiliar system, gather evidence for their case, and wait for their fate to be decided by the powers that be.

My job will bring me into contact with families at all stages of this process, but my main responsibility will be to support those whose refugee claims have recently been approved, journeying alongside them as they begin the process of integrating into the local community and helping them to find employment.

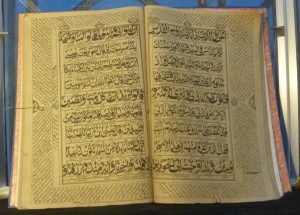

I start tomorrow, and I can’t wait. In the face of all the violence and hateful rhetoric lately, I am beyond thrilled to be able to extend the welcome of Christ to refugee claimants from around the world—Muslim and otherwise—who have come to this country seeking safety. I look forward to all of the beautiful people I will meet, and to all the ways they are sure to challenge and humble me and force me to grow, causing me to see more (and differently) than I did before.

I give thanks for every step a woman takes towards freedom and safety. I give thanks for every refugee’s safe arrival, and every successful application for asylum. I celebrate every small victory for justice in our world, and I recognize Christ’s coming in our midst. Still, I wait impatiently in the dark, willing these pin-prick stars to turn into daylight.

God, be born in our hearts. In our fractured world, let us be the midwives of goodness and truth coming into being.