I was happy to see the lively discussion in the comments section after my last

blog about literacy, subversion, and Paulo Freire, but realized from several people’s responses that some of what I am trying to communicate has been misunderstood. Some people seemed to think that I am throwing out everything I have previously talked about on this blog (especially Jesus) in order to focus exclusively on education as the answer for all problems faced by humankind. I want to clarify that this is not the case.

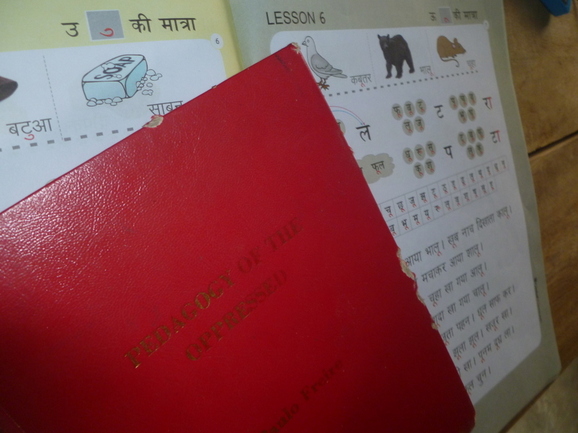

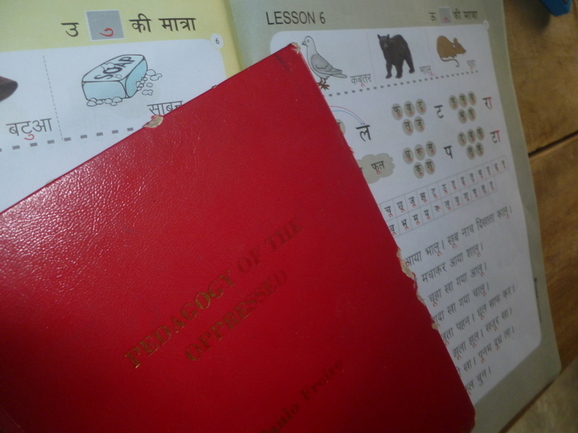

I am not saying that learning to read is an end in itself, or the key to human liberation. What I am saying is that learning to read is a means of nurturing critical thought, which is the starting place for human liberation. Many of us in the West have had minimal, if any, contact with illiterate people. Now that I live in a community where the vast majority of people cannot read, I recognize how much I have taken for granted the basic problem-solving and critical thinking skills that my education cultivated in me. Being able to read and write was the beginning of being able to learn about my world, to encounter new ideas, and to develop my sense of self as I expressed and explored my own thoughts, experiences, and opinions. So much of my faith has been mediated to me through the written word. Nearly all of my ideas about the things in the world that I have not seen for myself—economies, food systems, histories of entire societies, foreign countries and the ways that other cultures have interacted with my own—have come from books. It was through the written word that I learned about my body, how to care for it, how to understand what was happening when I got sick or caught an infection, and how to prevent or treat those problems when they occurred. It was through the written word that I learned about nutrition, about child psychology, about democracy. It was through the written word that I became employable. It was largely through the written word that I learned about Jesus.

Now imagine for a moment that you are not able to read your own scriptures. You are not able to read a newspaper. You are not able to look up information on WebMD, or to even read the prescription that a doctor gives you. You are not able to open bank account, to enroll your child in school, or to even write down the address of a friend or an office you want to visit. You rely completely on the local mullah or the rumors going around your neighborhood or the folklore of your grandparents to mediate the world to you.

Imagine how small that world will be; how your ignorance will prevent you from encountering any new ideas, from questioning anything you are told, or from seeking to change any of the destructive or unjust circumstances you find yourself in. Without a means of acquiring any information for yourself, and without the critical thinking skills to investigate the world and to form your own opinions about it, how will you ever know that there is a different way to live than the way that you and all the people you know are living right now? How will you begin to hope for anything?

That is the narrow, constricted world of many of my neighbors. That is why I think it is important for them to learn how to read: not so that I can simply deposit my worldview into their minds like empty containers, but so that I can empower them to think for themselves and have a chance of discovering for themselves the possibility of wholeness in their lives. If they are empowered to think critically and to consider new ideas, then we can dialogue together, learn from each other, and be a community that fosters spiritual, intellectual, and emotional growth. Dialogue will be something we engage in together, imagining new possibilities and shaping one another as equals.

It will take time, and I don’t know where that path of dialogue in community will lead, because I will not be the one controlling it. But I know that the path from ignorance to knowledge, from worthlessness to dignity, from blindness to sight—that path is the path to freedom. And it is only from a place of freedom that human beings are able to love. I believe God wants humans to be free agents capable of choosing love, rather than mindless followers who are motivated by ignorance or fear.

//

A few nights ago we attended a meeting centered around promoting literacy in India. An expert in the field was gave a lecture about the dismal failure of the education system to teach students how to read simple sentences or to recognize numbers 10-99 after several years of schooling, and then outlined the literacy curriculum she has designed to take Hindi-speaking children and adults from illiteracy to being able to read a newspaper in the space of approximately a month (A. and I have been trialing this curriculum in our slum with encouraging results). As soon as the lecture was over, a microphone was passed around the room and one dignified personage after another began pontificating about the reasons why the poor don’t want to learn, or aren’t learning. Each person was well-dressed and most of them were addressing the group in English, a conspicuous marker of education and status. Most of them were speaking authoritatively about the poor based on limited experience interacting with the people who worked in their homes as servants. We were sitting in an air-conditioned, wood-paneled room drinking chilled water from plastic bottles. Meanwhile, back in our slum (and perhaps the slums in which their servants live) the power was out and everyone was giving up on the idea of being able to sleep in the stuffy darkness with no air movement and temperatures still hovering above 90 degrees.

As is often the case with such meetings, well-intentioned wealthy people had congregated to applaud each others commitment to social causes and to take shots in the dark about to help the poor without consulting any actual poor people at all. Here we were debating the causes of illiteracy and the way forward, but there was not a single illiterate person in our midst, much less someone who could speak from experience about how they personally had managed to become literate in spite of poverty and the barriers it created. To me, this demonstrates a lack of trust in the poor; an assumption that they would have nothing of value to contribute to our discussion.

Of course, we were at this fancy reception, too, enjoying the air-conditioning and lavish food: wealthy foreigners among the wealthy. Yes, A. and I would go home to the sweaty power outage in the slum at the end of the night, and step over the kids from downstairs who fell asleep in front of our doorway trying to take advantage of any chance breeze that might sweep across the roof. We would breathe a sigh of relief in the unscripted familiarity of “home” after so much awkward social mixing. But the point is that we were invited to this elite gathering that our neighbors would have never been included in. We still move easily between the worlds of the downtrodden and the powerful because although we may have committed ourselves to the cause of the oppressed, we are not the oppressed. And like the elite philanthropists at the literacy meeting, I also struggle with a lack of trust of the poor—even though I have committed myself to my neighbors in many other ways. It would be bad form, bad development, to voice it, but sometimes we agree with our neighbors’ assessment of themselves: “You’re right—you may not be able to do this. It would be a lot easier if I just did it for you. Listen to my advice. Adopt my opinion. Listen to my idea. Become more like me.” We talk about empowerment, but deep down we’re afraid that our neighbors are just going to screw it all up. Their thinking is so narrow, their self-esteem is so low, their dreams are so small.

The poor carry with them the “deformities” of having been oppressed. Often their bodies have not fully developed because of malnutrition. Their minds have not fully developed because in addition to lacking food they have lacked opportunities for learning as well. Their sense of self has not fully developed because they have always been told that they are small, unimportant, and incapable. “Just let us do it for you, you can’t do anything to help yourself,” so many people have communicated to them when they’ve come in to “help.” “No need to think about creative solutions, we have the answer for you, because we are the ones who know,” others have insinuated when they come in with their ready-made programs, assuming complete ignorance and passivity on the part of the poor and never stopping to ask for input or participation. Because of all these factors working against them, poor people often do lack the confidence and the skills to help themselves, and they adopt the passive, dependent role assigned to them. Others’ lack of confidence in them inspires a lack of trust in themselves. The poor have been robbed of the very tools they would need to break free of this cycle: critical thinking to re-imagine themselves and their world, and to realization that their unjust situation “is not a closed world from which there is no exit,” but rather “a limiting situation which they can transform.” This can sometimes make our interactions with poor people extremely frustrating.

We who have enjoyed life’s advantages, on the other hand, are able to problem solve and plan ahead and think critically. We’re well-spoken and capable. But we carry with us the “deformities” of our background, too. One of these is our misconception that we are the ones who know… meaning that they are the ones who don’t know; they are lesser and can’t be entrusted with such an important and difficult task as transforming their lives! We need to be disabused of the idea of our superiority and independence so that we can become more fully human ourselves, by acknowledging our interdependence with others and allowing ourselves to be humbled and changed by our fellow human beings in community. If we want to acknowledge our neighbors’ full humanity and their innate human vocation alongside us as “co-creators” in the world, then we must be willing to work patiently alongside each other.