A few nights ago I went out with a friend to celebrate our birthdays, which fall just a few days apart. She is turning 19 years old. She had never visited a mall, or ventured even as far as the popular shopping street that lies just five minutes’ auto rickshaw ride from her house. I had floated the idea of going out for ice cream, and when we asked her older brother for permission (in the absence of her father, her brother is charged with the responsibility of keeping his sister safe and out of shameful situations), he suggested we go to this nearby market. My friend was immediately excited, because the shopping area includes Big Bazaar. She had been seeing commercials about Big Bazaar on TV for months, and it had long been her dream to visit the place herself.Big Bazaar is essentially an Indian version of Wal-Mart: clothing, household utensils and appliances, linens, groceries, and just about everything else you can imagine, all under one roof and available in air-conditioned convenience. Big Bazaar is quite a novel shopping experience if you’re used to bargaining with individual street vendors at a traditional outdoor market, and this Western, streamlined version is marketed as the place where “New India” (read: young, sophisticated, and modern India) shops.

I can appreciate the peace of mind that comes from fixed prices instead of a haggling process in which you aren’t guaranteed to end up with a fair price. I can also understand the preference for shopping in air-conditioned comfort instead of having to wander around outside. But there’s also something tragic about the idea of India’s traditional outdoor bazaars being replaced by a characterless alternative. Many of my neighbors take pride in their bartering skill; for them, haggling is an enjoyable game and an accomplishment to be proud of rather than a source of stress. At our local vegetable market, A. knows many vendors by name, and is friends with their family members. He sees them every day, and they often throw in a sprig of fresh cilantro or a handful of chili peppers for free, as a token of friendship. We were once invited to a wedding for one of the family members of our veggie supplier. At Big Bazaar, the suppliers are faceless and the check-out people are strangers. Everyone in the store is anonymous. But it’s not just the sentimental value of relationships or the communal feel of a local economy that’s at stake—it’s also local people’s livelihoods. Over half of India’s population is self-employed, and in my city that includes about 10,000 street vendors who sell snacks, clothes, chai cups, buckets, samosas, and everything else that’s available at outdoor markets. Besides those vendors, there are also thousands of small-scale entrepreneurs whose income depends on small shops, restaurants, tea stalls, beauty parlors, and print shops. If Big Bazaar really becomes New India’s main shopping destination, then that will mean thousands of “little people” going out of business in the wake of corporate consolidation… much like the effects of Wal-Mart on small towns in the U.S.

As we walked into the bottom floor of the tall building, my friend squeezed my hand tightly. “I’ve heard that they have those moving staircases here,” she said, “and there’s no way I’ll be able to walk on those!” I laughed. “You’ll have to,” I said, steering her towards the escalator, “because there’s no other staircase!” As we approached the bottom of the escalator, we noticed a middle-aged woman who was also preparing to brave the “moving stairs” for the first time. She stood nervously with her scarf over her head, tentatively stretching one leg out in front of her and pulling it back in a panic each time her foot actually made contact with the steps. “Come on, let’s go together,” I said, grabbing her arm. The two escalator rookies clung to each of my arms and hovered just behind me as I guided them forward onto the steps. Hesitantly, they made a dramatic leap onto the bottom stair and then wobbled precariously back and forth as it began to move, threatening to pull all three of us backward onto the ground. At this point we all burst into laughter: me at the hilarity of the situation; they at the relief of realizing they had survived and we were moving. It was only a few seconds, however, before they both realized that we were gliding inevitably toward an equally terrifying dismount. Anxious concentration gripped them and they in turn gripped my arms; with another awkward leap, they were safely on the terra firma of the second floor. Now we stood together in hysterics, along with the woman’s two younger relatives who appeared to be veterans of the moving staircase and had been awaiting her arrival at the top. Other shoppers cocked their heads in confusion as they passed, probably trying to guess the relationship between the foreigner and the apparent villagers.

As we walked around, my friend was in awe of the bright lights, the cold air emanating from the refrigerated section, the entire aisles filled with endless varieties of hair care products, soap, or laundry detergent. She marveled at the sheer volume of spices, vegetables, packaged snacks, and grains arranged in colorful displays. To her, the store was the picture of luxury, endless options, and prosperity. It was a sort of stepping-through-the-looking-glass experience of walking into the clean, shiny world of TV serials and cosmetic advertisements, but she was still living it vicariously; the jewelry, shampoo, or clothing that caught her eye was always shockingly expensive.

After our tour of Big Bazaar, we stepped into a couple of shops selling expensive wedding clothes so that my friend could look for Eid clothes, but I warned her that they would likely be very expensive. At the end of Ramazan, everyone who can afford it buys fancy new clothes to wear on Eid, similar to the tradition of Easter clothes that I grew up with. She seemed to enjoy holding up the beautiful dresses to herself in the mirror (again, just one step removed from actually wearing them). But after she had checked a couple of price tags I could also see that she was visibly uncomfortable with the attention of shop attendants since she knew herself to be somewhat of an imposter: there was nothing in the store that she could afford or that I would be willing to pay for.

We left the shops and wandered down the street admiring the carts of bangles, earrings, and deep-fried potato snacks. We passed several restaurants and a small table for a mehendi walla, with laminated photo examples of the intricate henna designs he would draw on women’s hands or feet, for a fee. We finally settled on Indian-style “Chinese” food at a small open-air restaurant for dinner, and over the meal I asked her what her favorite thing was that had happened between her last birthday and this one.

She looked at me with conviction. “Eshweety,” she said, in her endearingly stylized pronunciation of my English name, “This day is the best thing that has happened to me all year.”

“You’ve wanted to come here for a long time,” I said. “Is it the way you expected it to be, or is it different.?”

She fixed me with her intense gaze again. “It’s exactly as I imagined,” she said seriously. “It is wonderful.”

After dinner, we headed to an air-conditioned ice cream parlor for dessert. As we stepped through the doorway, a blast of cold air evaporated the sweat on our faces and necks. We sat down on a cushioned bench that ran the length of the back wall, painted with bright colors and studded with narrow windows into the attached restaurant behind. Our table faced the front counter where a rainbow of different ice cream flavors were on display under chilled glass panels. There was music from an old Hindi film playing. “It’s so peaceful in here,” my friend said in wonderment as she ran her eyes over the room. I slid a menu in front of us.

“What do you want?” I asked.

“Whatever you want. I don’t know,” she said.

The menu was in English, but even my translated descriptions were difficult for her to conceptualize. She had never heard of an ice cream sundae. I ordered two small sundaes to share, and I have to say, they were beautiful. It had been a long time since I had seen an ice cream sundae, either.

My friend was beaming. “Thank you, thank you, thank you so much for bringing me here! This is so great!” she gushed. “I will never forget this!”

It was 9:30 pm when we paid and stepped back onto the street. “I can’t believe I’m still out right now!” she said. “And by ourselves! I’ve never been out this late in my whole life.”

I laughed. “It feels free, doesn’t it?”

“Exactly,” she replied.

On birthdays, I usually ask people what their plans or hopes are for the next year, but with my friend I didn’t want to take away from the joy of this simple moment by pondering too long on the big picture or bringing up a reminder that there is little for my friend to realistically hope for, much less to plan for. She had wanted to finish high school, but that is an unfulfilled dream, closed forever: she dropped out last year to help care for her mother after her health seriously deteriorated. After being forced to abandon her studies, she joined a six-month tailoring course nearby, but family circumstances had prevented her from completing that, either. Her family is currently trying to arrange her marriage to some boy from a village out in the middle of nowhere. My friend will likely be married off by this time next year.

But that night, my friend was just a teenage girl experiencing the thrill of shopping at a mall for the first time, and she was giddy with excitement. To her, this outing was synonymous with freedom and maturity and the good life. I was happily amused by her enthusiasm, and thoroughly enjoying her big smiles after so many months of heavy conversations about her constricted world in which nothing is under her control and nothing seems to turn out well.

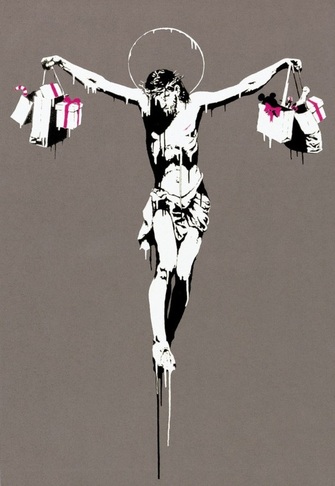

And yet… I was aware of a sadness, too, under my momentary enjoyment; a premonition of the dead-end of discontent in which this would all end. I want my friend to have more control over her own life, and more opportunity for new and interesting experiences. But I don’t want her to equate happiness with access to all of the shiny, expensive products we saw in the stores, and to feel that she will never be happy or important or beautiful without them. That was the underlying contradiction throughout the whole night: ambivalence about exposing my friend to more of this world when I knew that it would reinforce the idea of a “modern,” Western, consumer lifestyle being the pinnacle of experience; when I knew that it would encourage her to emulate the culture of higher-ups in society whose whiter skin and stylish clothes seem to make them “superior.” I didn’t want her to see the mall as a paradisaical antithesis to the slum, because that’s what all the ads and the daytime TV are trying to say, and it isn’t true.

How do I explain that I grew up with malls and movies and ice cream, but that the things I hold most precious in life have only begun to develop in the years since all of those things started to lose their sheen for me? The truth is that all the accoutrements that money can buy can’t fill an empty life with meaning or love, and I knew that many of the well-dressed women who brushed shoulders with us in the aisles of Big Bazaar probably didn’t lead lives that were much more free or fulfilling than my friend’s.