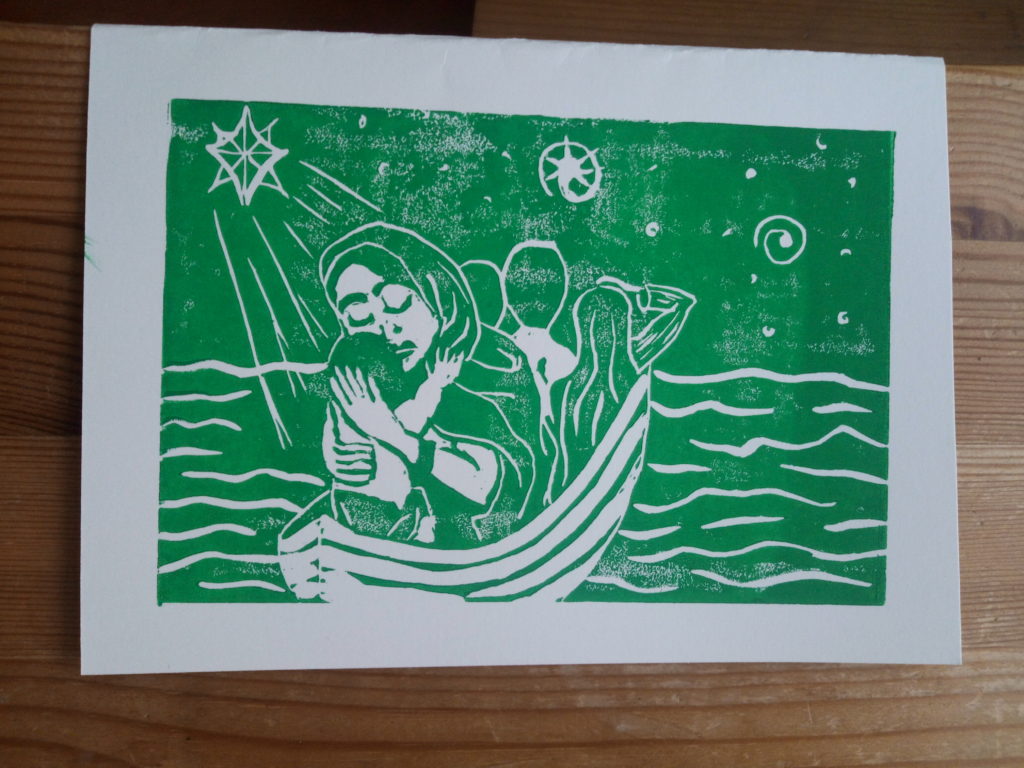

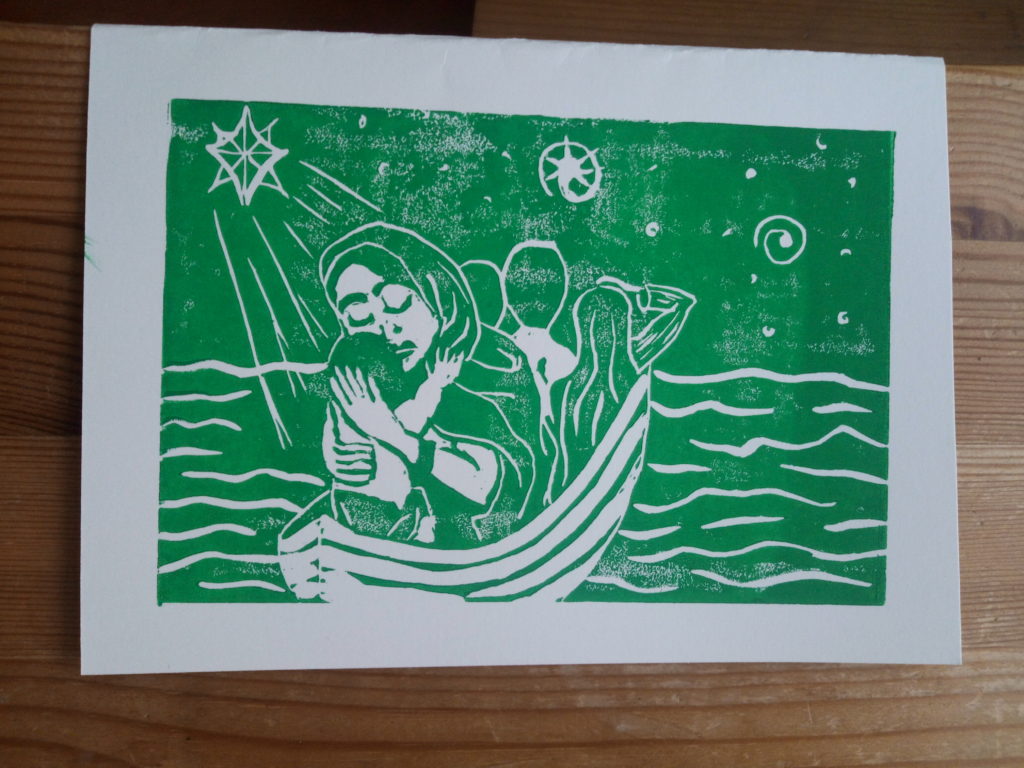

“Rohingya Madonna and Child,” A linocut print I made during Advent this year.

The weather in Vancouver has been cold recently. This morning is was -3 degrees Celsius outside, and frigid enough inside our apartment to see our breath as we looked out at the bare arms of the trees with the snowcapped mountains of the North Shore rising behind them.

We are drawing near to the end of Advent: the season of light; of hope and expectation–but also of longing. We are celebrating Christ’s entry into the world, remembering his humble, vulnerable entry into solidarity with his own creation as an infant. We retell the story of his undignified birth as an outsider in a city where few people were ready to welcome him. Perhaps, with the benefit of 2,000 years’ worth of hindsight, we imagine ourselves in the company of the shepherds, who heard and believed, or of the wise men, who recognized a king in the form of an ordinary village child and came to pay their respects. I’ve heard this story since I was a child myself, and instinctively I’ve always placed myself in the camp of those who were ready to welcome Jesus into the world.

But then again, all through this Advent season I have walked up and down the streets of my neighborhood past trees and houses strung with twinkling lights, and past homeless men and runaway youth who huddle under sleeping bags or sit collecting change in paper cups, the damp cold of the sidewalk seeping into their bones. This, while tens of thousands of homes sit empty across our city, offering passive income to investors rather than shelter to people who need it.

I follow the news about Rohingya refugees who are being raped, burned alive inside their own homes, and hacked apart with machetes. Some live through horrible violence, and–after fleeing with their elderly grandparents and newborn babies in tow–cross the border to the relative safety of Bangladesh to be turned back to the hell they have just fled by border guards who are “just doing their job.”

I read about the fear and suspicion running so rampant in the country of my birth that the nation as a whole is turning its back on refugees, slashing the number of people who will be resettled annually by more than half and passing laws to keep people from many parts of the world out of the country all together.

I look around and I realize that we still live in a world where there is often no room for the vulnerable members of our society who represent Christ in our midst. We still live in a world where Jesus is often met with the cold dismissal: No room.

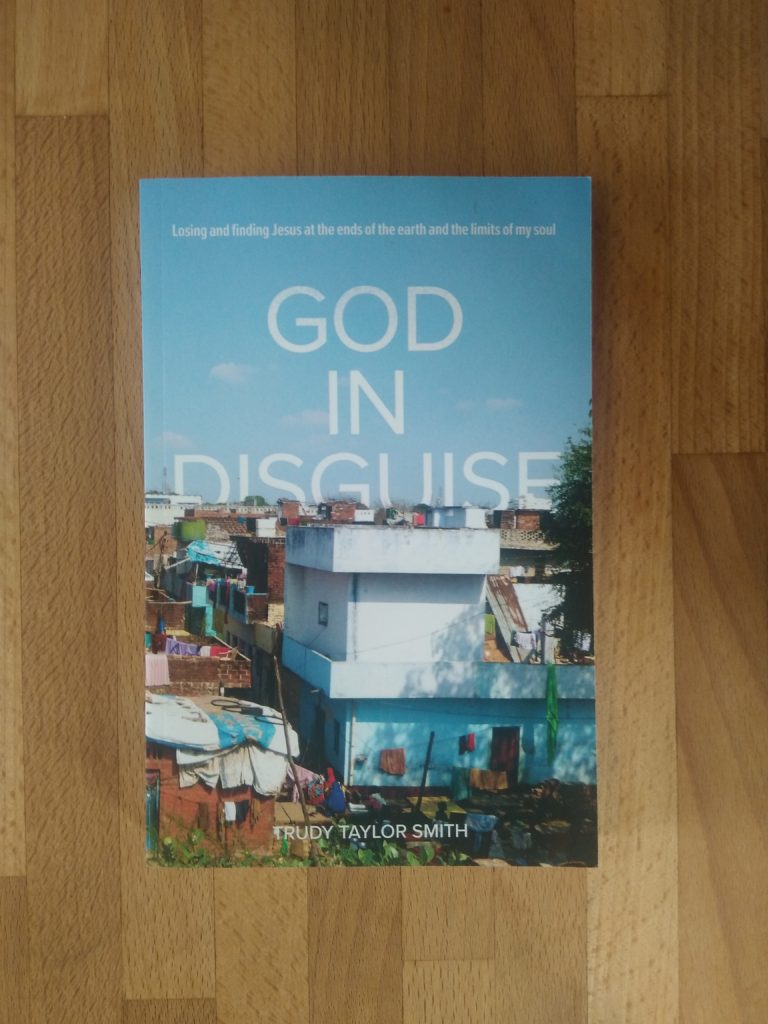

So as I prepare to celebrate Christ’s coming on Christmas day, I think long and hard about how I can make room for Christ in the middle of the cold winter we find ourselves in right now, and how we as a society can extend welcome to Him in all of His distressing disguises.