Walking along the side of the road is strange at this time of night. I’ve never seen it so utterly desolate and quiet. It feels as though the city has been emptied of its entire population. Fortunately, before we have to walk too far down the road, an auto pulls up and we climb in to ride the rest of the way to the train station. The station, by contrast, is as busy as we’ve ever seen it: a colorful swarm of sleeping bodies covered head to toe under thick quilts and blankets take up two-thirds of the platform, making it difficult to squeeze past. Around 5 am, our train arrives, and there’s confusion as we all crowd around, trying to board. All the doors are locked, so following the usual protocol, one or two passengers force open a window and climb through to liberate the train car from inside. Then we’re all pouring in, but there are no lights on so we struggle to find our assigned bench in the dark, while other passengers merely look for whichever seats aren’t occupied yet in order to claim them temporarily with their luggage. Even though we bought our tickets a month beforehand, the only thing available was this “bench” class: berths of hard, straightback pews facing each other, designed to fit three to a seat, but bound to be stretched beyond their official capacity because every person holding one of an unlimited number of “general” (read: “standing”) tickets being sold will also be accommodated in this train car. For awhile, there are just the two of us sitting on our bench, and we are naively hopeful. Perhaps our main challenge over the next 10 hours will just be existing on this uncomfortably hard seat and maybe managing to fall asleep for part of it!

Then comes the next station. And the next. People fill in the aisles, and then flow in between our benches, standing in the spaces between our knees and leaning over us to support themselves with their hands on the backs of our benches. Eventually the car is full, as far as we can tell. Even making it to the toilet at the end of the car is a pipe dream, unless you want to be crowd surfed to your destination. And yet somehow people continue to pile on– they find space for new people long after Westerners would have declared that an impossibility. Now we reach the stage where there’s a fight at the door every time we reach a new station. The least fortunate of the new arrivals merely hang out of the open door with their luggage on their backs as the train accelerates out of the station, and eventually, they are absorbed into the car. But finally, even this magic runs up against the laws of physics: a young man with a big backpack sticking out behind him is stuck outside the door as we pull away from the station. He’s just an inch or two away from running into the signal poles each time the train passes one of them, and five minutes after leaving the station, he is yet to move one inch into the interior of the train. As we look out the window, we can actually see the backpack of the person ahead of him also sticking out of the train door, in front of his face. We call out to him and A. reaches through the window to relieve him of his bag by tying it to the bars of the window from the inside. The bag and the man stay where they are for the next hour or more, until they reach their final stop.

Sitting next to A. during this whole ordeal is a grey-haired Indian man who seems wealthier than the usual bench-class passenger and seems to be taking it all in as an adventure. He’s generously inviting more people to come and stand in between our benches, or sit on the edge of our bench, or to pass their babies and small children into our compartment to sit on someone else’s lap while their parents stand wherever they find room. He’s obnoxiously friendly like that. Meanwhile, I’m becoming internally militant over defending my shrinking space as another grateful passenger squeezes onto the seat and my shoulder presses harder against the bars of the window. By this point, a couple of people have stowed their seven- or eight-year-old boys on the luggage rack overhead, and I envy their apparent comfort. Observing the general scene, the overly-enthusiastic passenger turns to A.: “It’s miserable, isn’t it?” he says happily. “Why did you come to India?” he wants to know. A. bursts out laughing. “It’s very discomfortable,” the man continues in English. “Everyone is discomfortable.”

“Discomfortable” indeed. But whereas most people in the train car were expecting the journey to be exactly like it was, we were comparing the experience to the thousands of other journeys recorded in our memory which were faster, easier and just more comfortable than this one. When a young woman in a sari sat down in the floor directly in front of my seat where my legs should have been, she was probably thinking, This is how it always is on the train. But as I resigned myself to the lost leg-space and curled into a vertical fetal position on my last square foot of bench, I was thinking, This is the worst trip of my life. Expectations are everything.

It was a small comfort to think that we were sharing in the experience of the Majority World by traveling the way most human beings in the world do—I was reminded of this every time I looked out the window to avoid mounting claustrophobia and saw motorbikes, buses, and jeeps that were just as packed full of people as our train was.

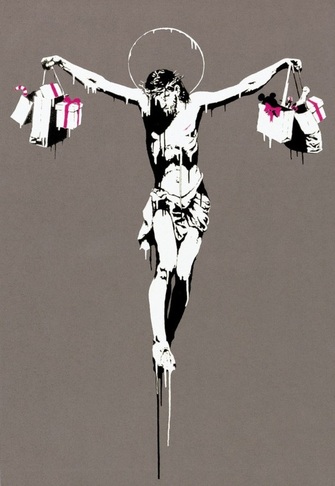

Still, we were eager to get off the train. We spent the night at a cheap, grimy hotel in Delhi, and the next morning the second leg of our journey began. Arriving at the airport, we already felt that we had crossed into another world. It could hardly be imagined that the air-conditioned spaciousness of the airport with its glossy surfaces and orderly lines and uniformed personnel was really India, separated by just a few yards of space from the messy, pulsing life continuing all around it. Stepping into that other world felt like a relief, but it was also very strange. This surreal feeling continued as we boarded the plane, settled into comfortable chairs reserved just for us, and watched movies for a few hours before touching down in Istanbul. Our minds couldn’t keep up with the distance our bodies were traveling at such an incomprehensible speed. The Turkish airport was like an upscale shopping mall. How could Turkish coffee and baklava and Western fast food chains really be just a few hours away from chai on the train with snatches of rural Indian life flying past the window outside: villagers plowing their fields with oxen and harvesting crops by hand; entire families working at brick kilns with the tall smokestacks in the background, just like you see in those documentaries about modern-day slavery. Then we board the next flight: plastic-wrapped blankets, plastic-wrapped headphones, plastic cups for water and juice and coffee. Complimentary socks and slippers and warm towels and entrees containing more meat than we’ve eaten in the past month.

Things get stranger still when the in-flight map shows that we are no longer flying over Pakistan, Afghanistan, Turkey, or France but over the American South—yet by now we have accepted this liminal space that defies comprehension. We land in my hometown, are greeted by family and a peppermint mocha from Starbucks, and minutes later we’re cruising down the open highway in an SUV, trying to get our bearings as we take in the big box stores, billboards, and miles of open space. Christmas lights. Suburbs. Indoor grocery stores full of flawless, giant fruit and food imported from around the world. It is just 48 hours since we set out from the slum. The geographical distance we have just traveled doesn’t even begin to represent the full distance we have covered.