We're Not in Canada Anymore

Our last week in Vancouver was good. We felt a sense of closure with our last community dinner, last Vancouver sushi run, and last evening of casually hanging out in living rooms with friends. It feels good to be moving onto the next phase, but it was sad to say goodbye to our housemates, our teammates, and to the rest of the community– we miss them already. It’s interesting– we probably have less in common with most of the people in that intentional community than we did with our college friends, in terms of background, life experience, etc. But it has been a really rich experience to build deep friendships with people that are based on our common passions and convictions and our choice to live together rather than just becoming friends out of situational proximity (happening to be in the same class, or dorm, or city) or because we have a lot in common. We are inspired by the humble way that they are turning their little corner of the world upside-down every day, and by the quiet but stubborn defiance of injustice that runs through even the small details of their lives. It’s encouraging to think that we’ll see most of them again.

Our time in Vancouver has been a season of rhythms. Rhythms of cooking, cleaning, eating, and praying together; rhythms of work and rest, social time and solitude. Weekly date nights and weekly Sabbaths. I hope we can carry on some of those rhythms of prayer and rest as we go back into Nomad Mode for the next few weeks.

Source: New feed

Tibet

Although our worldview does not condone suicide, it is inspiring to see people so committed to seeking justice and promoting truth that they are willing to do whatever it takes– even accepting horrible suffering and violent death– to pursue what’s right. As disciples of Love Himself, we are challenged by this kind of spiritual commitment– how much more reason do we have to sacrifice, since we hold the promise that if we lose our lives we will find Life? We are also moved to pray for all those whose lives are being destroyed in the violence and for those in China who have become active and passive participants in the unfolding terror through their ignorance and hatred. Please join us in our prayers.

You can read about the current event in Tibet here on CNN or here in the New York Times. If you want to get a better understanding of the history of the Chinese occupation of Tibet stretching back to the original invasion in 1950, Tibet: Cry of the Snow Lion is a very engaging and informative documentary with a lot of great footage and interviews with Tibetan monks, nuns, and foreign observers who have experienced the brutality of the Chinese regime firsthand. You can watch that documentary here for free.

Source: New feed

Life and Death

This week we visited a very bright, tropical city—which is another way of saying that it is very hot and humid. We visited a slum where people had built bamboo huts for themselves on the side of the road, next to a murky black canal that could serve as a toilet. We visited a slum where the original bamboo huts had been replaced with a giant concrete building which was darker and more crowded than the original huts, which still provided no toilets, and which took away the possibility of the residents raising goats or other animals for food as they had done before. We visited a big slum community that was built around a garbage dump, where the residents told us that there is significant flooding for three months out of the year, and where we saw for ourselves that the public toilet (meant to serve hundreds of people) was so filthy that it had become totally unusable. A fire there had recently destroyed more than one hundred homes, so more than a hundred families are living in tents after losing whatever meager possessions they have ever owned. In still another community, we saw children whose skin was covered with rashes and some of whom had strange skin infections, presumably due to lack of clean water and generally unhygienic conditions. One boy stood out to us in particular—he couldn’t have been more than twelve years old, but he was unmistakably ill. His eyes were yellowish and sunken. One baby stood out to us in particular. She was 14 months old, and very, very skinny. Babies aren’t supposed to look like that. Her mother’s face looked tired and resigned as she fed and held her baby, and as I watched them I thought, What must that feel like? To know that your child is sick, or wasting away, and that you have no power to do anything about it? I was chilled by the idea that many of the people we were seeing and talking with may not be in this world much longer.

Later that day at the train station, the point was driven home. As we stood outside the train station we were shocked by the sudden realization that for the past several minutes we had been standing together and chatting just a few feet away from two dead bodies lying on top of makeshift bamboo stretchers. Human-shaped lumps under white sheets with rigid feet sticking out at the bottom. Were they people who had been hit by trains? we wondered. No, they were probably beggars who had eventually died inside the train station from old age, or hunger, or parasites, or some other disease. People who had been neglected their entire lives, and who were being neglected still as they lay there in the solemnity of death while the rest of us casually carried on with normal life around them, talking, laughing, failing even to notice their presence.

The idea of those unknown people dying alone and then having their bodies collected by a stranger and left outside was quite disturbing to us. It is a good reminder of why He came into the world and of why we have come to this part of the world. But we have a long way to go in following His example.

“The one thing that Jesus was determined to destroy was suffering: the sufferings of the poor and the oppressed, the sufferings of the sick… But the only way to destroy suffering is to give up all worldly values and suffer the consequences. Only the willingness to suffer can conquer suffering in the world. Compassion destroys suffering by suffering with and on behalf of those who suffer. A sympathy with the poor that is unwilling to share their sufferings would be a useless emotion. One cannot share the blessings of the poor unless one is willing to share their sufferings.”

— Albert Nolan, Jesus Before Christianity

Justice redefined

A few hours into the journey, an elderly woman walked through the train car, begging for change. She looked frail and tired, and she had scabs on her arms. Lots of people get on and off of Indian trains along the way, begging or selling things, but when I noticed her standing in the aisle after she had made her rounds, I realized that she had nowhere to sit until the next stop, and who knew when that might be. I willingly offered her my seat. She hesitantly accepted, but seemed grateful to sit down. Over the next few minutes I learned a little about her life and tears welled up in her eyes as she talked about the plight of the four children she is trying to support by begging on the trains.

After she left, I turned to my companions with new eyes—those interlopers who were sitting where I was supposed to be laying down, making up for all the sleep I hadn’t gotten the night before. Actually, their clothes were not much better than this old granny’s. Some of them were pretty old. They probably got “waitlisted” because they couldn’t scrape together enough money to purchase their tickets far in advance like us wealthier people can. So why had I felt such compassion towards the elderly beggar, but only anger and indignation toward my fellow passengers?

I think it came down to my sense of justice.

Justice. Jesus told a story about justice. It was a story about day laborers (Matthew 20:1-16). A land owner goes out to the market early in the morning to hire some of them to work in his vineyard, and agrees upon a certain wage for the day. Throughout the day he goes back to that same spot and hires more and more of the men who are still standing around waiting for a job. By the end of the day, some of the men have been working outside through the heat of the day, while others have only been working for the last hour or two. The land owner pays the latecomers first, and when the morning crew sees that he’s paying them the typical wages for a full day’s labor they start to get excited, because they assume that must mean that he is planning to pay them even more than what he originally agreed to! When their turn comes and they receive the same amount as the last men who were hired, they feel that they have been wronged. “That’s not fair!” they tell the boss. “These guys got the same amount of money for an hour of work as we got for a full day of sweating out in the sun!” The land owner’s response challenges their sense of injustice. “Have I not compensated you fairly for a full day’s work? Why does it matter to you if I want to give these other workers a full day’s wages, too?”

The situation for day laborers in India and under highway overpasses across America today is similar: if a day laborer was still waiting for a job in the market at the end of the day, it meant that he wouldn’t able to feed himself and his family that night. The land owner in Jesus’ parable wasn’t paying people what their labor deserved—he was paying them based on what they needed to survive that day. This gives us a huge insight into God’s idea of justice.

In His view, Justice is not people getting what they deserve.

Justice is people being provided with what they need.

Our companions on the train needed a seat just as much as we did. God doesn’t care whether their tickets were waitlisted or not. He didn’t care that the woman who was begging hadn’t bought a ticket at all. And neither should we.

Source: New feed

Snapshot of Daily Life

Up to this point, A. and I have been doing most of our long-distance travel on the modern, air-conditioned metro system, but most of our neighbors are limited to the un-air conditioned and less reliable bus system because it’s cheaper. So last Wednesday we decided to take the bus to our friends’ place on the other side of the city. We piled into a crowded little van (but van is a strong word… it implies full enclosure) for the first unpaved leg of the journey, out of our community to the highway. Then we waited for nearly half an hour at the bus stop. While we waited, a very crowded bus came by and a few people scrambled on, some still hanging outside the door and trying to force their way inside as the bus sped away. Finally, ours showed up and we piled on. It was crowded and hot, but we were excited to be above ground and able to see all of the street-level activity between point A and point B. A few minutes down the road, a rhythmic, jolting, thudding starts under the floor of the bus. We look behind us to where the last passenger aboard is standing in the doorway, clinging to the outside of the bus. He is looking down at the tire, and seems somewhat amused. The motorcycle and truck drivers passing us are all staring in that direction, too—apparently the tread is coming off the tire and flinging against the bottom of the bus with each rotation. At the same time, we’re beginning to notice the grinding of the gears and the halting acceleration after each stop of the bus. We aren’t sure which problem will take down the bus first. As we’re sitting in a traffic jam at a huge, unregulated intersection with a cross flow of rickshaws, motorcycles, trucks, cars, and buses in front of us, we stare into the rooftops and inner rooms of the slum dwellings that line the highway, divided only by a canal of open sewage and huge pipes serving as walkways over the water. A man repairs a power line standing on a bamboo ladder whose bottom rung is just a couple of feet away from our back tire. Pedestrians and bicycles hurry past between the tire and the ladder. A few minutes later, the transmission beats the tire to its demise and everyone moves from our bus to another one further ahead in the traffic jam. This one runs on a slightly different route, but we manage to get off at approximately our desired destination and take another “van” to our friends’ community. After all of that, we still manage to reach their front door in less than two hours!

Yes, life here is good.

Source: New feed

Our own place

Source: New feed

Mountain Retreat

We spent a lot of time hiking to and from class, and exploring the surrounding area. The town is a hill station from British colonial times (makes sense that the British would build their fancy estates in the part of the country where the climate most closely approximated that of England), so there are lots of interesting old buildings around, but by far the most interesting element of the place was the wildlife. There were wild monkeys all over the walking paths and playing in the trees, and leopards are often sighted in the area… though we were spared the privilege of running into one of those.

While I was sitting in the hospital room alone one day, checking email, I made the mistake of leaving the window open for too long. After a few minutes, I looked up just in time to see this kind of monkey (the more aggressive kind) slowly raise his head up into the window:

After the reprieve of the mountains, it was a bit of a shock to careen back down the mountain and into a sweaty traffic jam with nauseating fumes, but we’ve pretty well adjusted again now. And we made it home in time to celebrate our 2 year wedding anniversary on the 26th! Looking back on everything that’s happened, it seems like it’s been far longer than two years… we’ve enjoyed the adventure so far and are excited for the journey ahead.

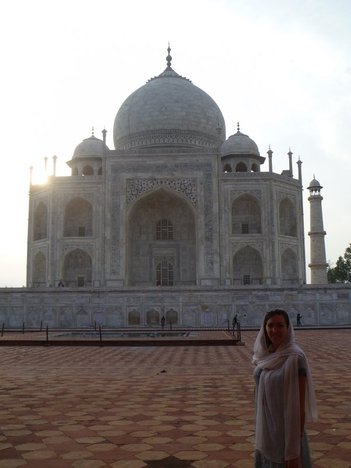

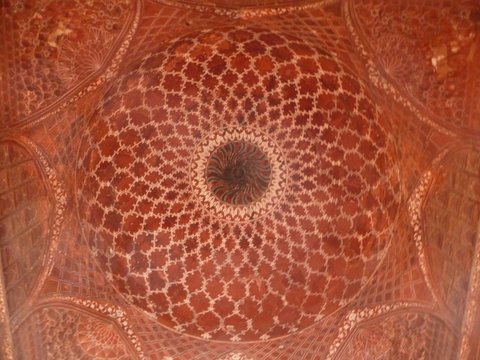

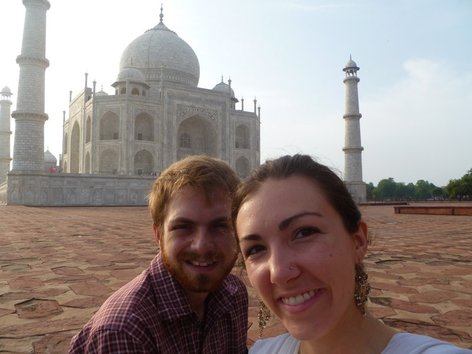

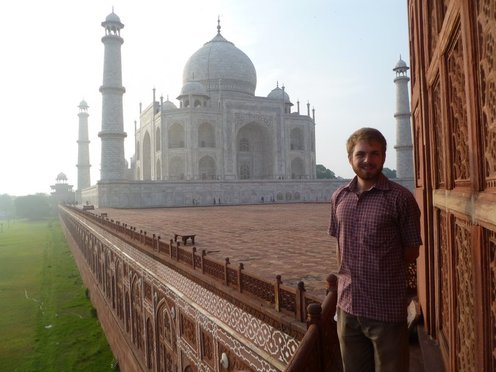

Since we were in the neighborhood…

Growing Pains

Of course it’s not all peace and quiet. As usual, the monkeys are everywhere, both the aggressive and the space-suit variety, and we had a nasty run-in with a troop of them the other day when we came to a part of the road where they refused to let us pass. A. wielded a water bottle and made aggressive noises, but the monkeys just leapt forward and bared their fangs. We retreated to find stones to throw at them, and once we had pebbles in hand the monkeys fled– though not without indignation. A momma picked up her baby just as I hurled a little rock in their general direction and turned to look at me with her mouth gaping open, as if to say, “Hey, this is a baby! What do you think you’re doing, being so aggressive?” The next day, we saw a local guy chasing a monkey troop away from the street in front of his shop with a flare gun, so I guess foreigners aren’t the only ones being monkeyed with around here.

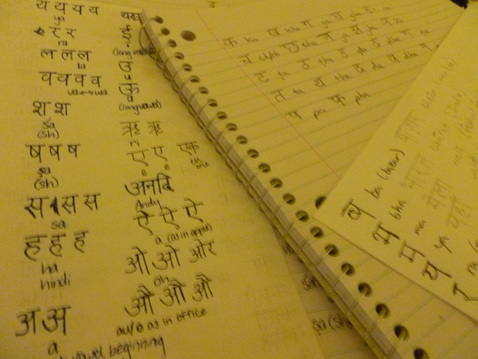

We have two hours of one-on-one language instruction each day, which is really pushing us forward in our listening and speaking ability, and our time thus far has felt extremely productive. We’re encouraged by our progress and thankful for the formal instruction and the change of scenery. But there’s an element of being here that is difficult, too. Having access to internet in our apartment (whenever the fog or thunderstorms aren’t knocking it out) means greater “connectedness” with the outside world– we can read online news, skype with a few people, send emails, check facebook. But in another way having that connection shows us just how disconnected we really are. We can digitally follow bits and pieces of hundreds’ of friends’ lives, but we aren’t part of the day-to-day substance of any of them. The reality is that “back there” isn’t really home anymore, and “over here” isn’t quite home yet. So this week, even as we take in the beauty of the Himalayas and the excitement of preparing for the next step of our journey here, we’re also feeling the loss of the life we left behind and missing the people who have journeyed with us up to now– people spread across the globe from China to California to Nashville to Peru, and lots of places in between. A week from now, we’ll be on the move again, as we have been many times before. Uprooting has become somewhat of a trademark for us, but we’re hoping soon to begin learning the patient art of settling in.

Source: New feed