Source: New feed

Source: New feed

We firmly believe that this is an issue that everyone should be able to agree on, regardless of our political or religious persuasions. Both political parties have supported (and expanded) the drone program, but the implications of it are so anti-human that this continuing phenomenon demands the attention– and the resistance– of people of compassion. With that goal of stirring compassionate people (and especially followers of Jesus) to action, A. and T. have co-authored this post to look into the human cost of drones, as well as to examine the question of whether this “anti-terrorism” strategy might actually be increasing the risk of terrorism in the United States and around the world.

A couple of months ago, we read an interesting Kindle Single called Aftershock: The Blast That Shook Psycho Platoon (download it for free here) about some of the struggles US soldiers face as they come back from either Afghanistan or Iraq. It talks about the effects of two conditions: post-traumatic stress disorder (PSTD) and mild traumatic brain injury. Aftershock follows the lives of one platoon that experienced a rocket attack while they were in their barracks at a main base in Iraq. The rocket barely missed their building, and fortunately, only one of the men experienced minor physical injuries from shrapnel. Unfortunately, all of the men experienced some psychological injuries from the distress of a near-death experience and from the blast waves emanating from the rocket. Research is showing that the explosions of these bombs, land mines, and rockets can rattle the brain so much that the end result is like a concussion. Concussions are dangerous enough for football players or other people who suffer accidental head trauma, but the Army’s researchers are finding that concussions are even more severe for soldiers since usually the concussions are sustained in the middle of combat when a flood of chemicals like adrenaline are surging through the brain.

Concussions are strange and unpredictable injuries: some people experience no long-term effects from them at all, while others experience headaches, memory loss and other life-altering symptoms. When these brain-altering injuries occur during traumatic events– like losing friends and fighting for your life in battle– they can be compounded by post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Over the past few years, the combination of those two conditions has manifested in many (but certainly not all) returning war veterans as an inability to adjust to civilian life, irrationally violent behavior, and suicide (the VA estimates that 18 U.S. war veterans commit suicide every day).

Not only does it create more enemies for the United States by tarnishing the country’s image abroad and boosting Al-Qaeda’s recruitment, it also sets a dangerous precedent for other nations to follow. Will the world become a safer or more dangerous place if nations like Iran, North Korea, China, and others follow the example of the world’s leading superpower by using drones to carry out extrajudicial killings inside the territory of other sovereign nations with whom they are not even at war? By the low standards we have set thus far, Iran theoretically has the right to strike Israel with drones (which they are acquiring) in the name of national security, and China is entitled to use drones to kill off the pesky Taiwanese or Tibetan leaders who threaten its regime’s power. I think we can all agree that those are some absurd and terrifying possibilities.

But hopefully as the Body of Jesus we can sense more than irony– hopefully the Spirit will open our eyes to see the injustice of murdering innocent people, especially children, in our endless pursuit of greater security for ourselves and our children. Hopefully we sense the danger in ignoring human rights, human lives, domestic and international law in the name of defending our rights. God willing, we will recognize that this violent disregard for the lives of people from a culture and a religion not our own actually cheapens our regard for our own lives and makes a mockery of our supposed devotion to the God who created us all, who imprinted us with His image, who lived and died as one of us, and who declared that He is forever present in the enemy, the outsider, the needy and the rejected ones.

Our prayer is that as the community of Jesus, we can take up our cross and find creative ways of practicing the active nonviolent love that Jesus taught us, and that we can find the courage to stand against our society as an example of self-sacrificing love in an age of paranoid retaliation.

Source: New feed

It felt strange to say goodbye to the neighbors and friends that we’ve gotten used to seeing every day (some of them multiple times per day): a mixture of sadness and anticipation and plain old relief. The truth is that I’m tired. I’m tired of seeing so much suffering and pain, tired of struggling so much against unjust systems that have no heart and no mind; of being drawn into the chaos of other people’s lives, often able to offer no real solutions or help other than to be along for the ride with them. I’m looking forward to some silence and some open space and some rest.

But that time is not yet. For now I’m enjoying the relief of some time away from all of the noise and activity to be refreshed and to reflect on all that’s happened and all that is ahead. To relax in the knowledge that it is God who brings justice and transformation, and not me. To remind myself that God is still at work in my absence, just as He was before my arrival.

Source: New feed

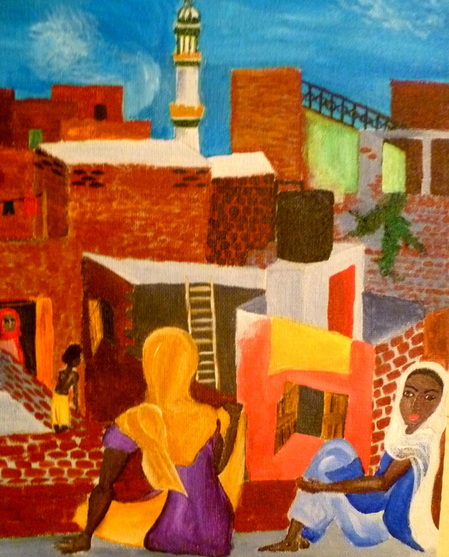

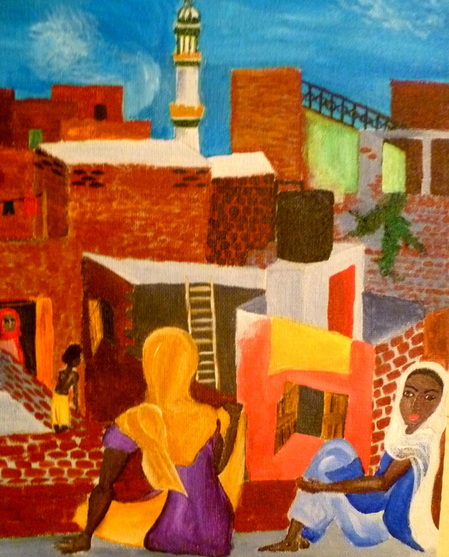

More and more life all the time, actually– this week, two new babies were born in our community. Yesterday afternoon, drummers came to pound out a beat in front of one family’s house; an excited crowd gathered in the alley around their door, and the new baby’s relatives took turns dancing in the middle. That night, the other family hosted a party and gave out dinner and sweets to celebrate new life. It seems that whatever is going on in people’s lives and families, whether deaths or births or weddings or arguments or celebrations or grief, it is usually shared with others.

In Luke chapter 10, Jesus is cross-examined by an “expert in the law” who wants to know what he must do to “enter into life.” Jesus’ reply is simply to direct the man back to the words he has already read hundreds of times in the law: “Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your strength and with all your mind”; and, “Love your neighbor as yourself.” The man had intended to engage Jesus in a theological debate, so he is disappointed with this straightforward response. Flustered, he searches for a way to make things more complicated—and to relieve himself of responsibility: “Who is my neighbor?” he asks.

This morning, for the first time, this man’s question struck us as odd. These days, waiting in line for the outhouse together, sharing laundry line space, talking at the doorway and through the walls, eating together, experiencing the rain and the power outages and the festivals together, there is no way that we could ever be confused about who our neighbors are. We often fail at loving our neighbors as ourselves (particularly the ones with whom we share the closest quarters!), but our lives are so intertwined with theirs that it would be impossible for us to ask who our neighbors are. This man’s question to Jesus reveals that he was probably living in such isolation from the people—and the needs—around him to the point that he could really look around without seeing any “neighbors”. Put enough walls and busyness between you and the people around you, and you will become oblivious to the demands and joys of neighbor-hood with other human beings!

As humans, we are dynamic rather than static beings, so learning to recognize our neighbors and become neighbors to other people is not a matter of static location somewhere on the continuum between solidarity with our neighbors and isolation from them. It is a question of movement—with each decision we make, about where to live, and how to live, we can move either toward greater solidarity with others, or greater isolation. There is no set expression of what this movement will look like for each individual, as we all begin in different places (and even living in a slum does not guarantee that we will consistently choose to move toward solidarity rather than toward isolation). But the movement is the important thing.

SOLIDARITY <—————————————————————-> ISOLATION

We are learning that Jesus calls us to live life in such a way that the question of, “Who is my neighbor?” becomes irrelevant because we are already living life alongside the diverse lot of strangers, enemies, and friends whom we have recognized and accepted as our neighbors.

Who is my neighbor?

This week I went to visit two young friends I had met at a women’s literacy class in our community. They’re sisters, aged fifteen and eleven, and their parents have both died over the last few years, so they live with two older brothers who work to support the family. When I arrived at their home, they offered me a piece of a samosa. In the course of the conversation afterwards, I learned that because of the rain their brothers hadn’t been able to work for the past couple of days, and so this one salty pastry split between the three of us was all they had for lunch! They were waiting for their brothers to come home that evening with enough money to buy something to cook for dinner. This was sobering enough, but then one of the girls took me over to her cousin’s house just a few alleys away and left before her relatives fed me more samosas, along with chai and sweets. It is frustrating that I was treated to this hospitality while just a few yards away the girls were going hungry. Upon reflection, the disturbing thought occurred to me that my friend may have intentionally taken me to her cousin’s house thinking that was the best way to treat her guest the hospitality she herself was unable to provide. It’s humbling (and yes, disturbing) to think that the poor are feeding me instead of feeding themselves.

A lot of people go hungry in our neighborhood on a regular basis. Especially with the rain interrupting so many people’s livelihoods recently, we’re coming into a deeper awareness of that. But the fact remains that in all kinds of weather, families are living on the edge and often skip meals. Stunted children and skinny babies are the most visible reminders of that. Living within a few meters of these families, we never go hungry and make our decisions about meals based on our tastes rather than on whether or not there is cash on hand to cook a meal.

Of course there are all the complexities of an unjust global system that has kept me and most other Americans well-fed for our entire lives at the cost of keeping others hungry—but my friend has done a compelling job of explaining all of that in his blog post (which I highly, highly recommend), so I won’t go into that here.

Right now, I’m living next door to hungry people, so there is this pressing question of how to genuinely love my neighbors when they are hungry and I am fed. What is in my power to do, and am I doing that? But actually, in this age of global food chains and international connectedness, I suppose that my question is no different from the question we should all be asking—because whether we live in Los Angeles, Houston, India, or anywhere else on earth, our neighbors are hungry while we are fed.

Jugar is a teenage guy plugging a leak in our water drum by scraping off pieces from a waxy bar of soap and applying it to the hole in the plastic like putty.

Jugar is fitting 14 adults into a three-wheeled taxi during rush hour—even though two passengers are without a seat and one of them is mostly outside the vehicle hanging into traffic—because there’s no other way for everyone to get home.

Jugar is a man somehow making a living by painting monkeys as leopards and peddling them through residential neighborhoods as entertainment.

Jugar is someone transporting a live goat across town by slinging it across their lap on a motorcycle.

Jugar is a family opening a restaurant even though they don’t have a building, a sink, or a stove, and yet somehow managing to keep up with business by cooking over a wood fire inside of a handmade mud oven, seating customers under the same tarp that will shelter the whole family overnight.

Jugar is converting a cycle rickshaw into a school bus to carry 10 or more children to and from class each day.

Jugar is making chai with salt instead of sugar because you can’t afford sugar but you still need to serve your guests tea.

Jugar is our friend finally succeeding in receiving the college diploma she has rightfully earned– without paying a bribe– by overturning a corrupt official’s desk in frustration after months of unsuccessful visits.

Jugar is the mobile store man repairing our phone by scrubbing the hardware with paint thinner and a toothbrush after we accidentally dunked the whole thing into a cup of hot tea.

Basically, jugar is finding a way to accomplish what is necessary in spite of any logistical, natural, or bureaucratic barrier that may present itself, and India survives on the determined, implausible, ingenious improvisation of jugar every day.

I suppose that our decision to move into a slum was a huge act of faith in the first place. It was a choice to live in hope that God will bring transformation, and a declaration that we are so convinced of that inevitable change that we are willing to stay here until it happens. I know that as they struggle with hunger, sickness, abuse, and systemic injustice, a lot of our neighbors feel hopeless about life ever changing. But today it occurred to me that in Mark chapter 2 when that paralyzed man was lowered down to Jesus through the roof of a packed house in Palestine two thousand years ago, it was because of his friends’ faith that he was healed. Who knows whether he was feeling confident in that moment of whether he would be healed or not, but his friends were certainly taking some drastic action on the assumption that he would be. Perhaps his own mind was ablaze with fear and skepticism, but that mustard seed of faith from his friends was enough. And I wonder if maybe that can be the kind of faith that we hold on our neighbors’ behalf here. If there are even just two people out of the thousands in our neighborhood who believe that transformation is possible, is that enough? Is that the mustard seed that can grow into a wild, vibrant mustard plant and take over the garden? I’m living on the assumption that it is.